Shari Bernstiel always wanted a horse. Even when she began

losing her sight in elementary school, she begged her mother for

a pony every year for her birthday.

"She'd say, 'Where would we keep it?' " said Bernstiel - a

good question, considering that the family lived in a townhouse

in North Wales. "I'd say, 'I'll keep it in my bedroom.' "

In December, Bernstiel, who is legally blind, got her wish,

though it's not exactly the horse of her dreams. Tonto is a

27-inch miniature horse Bernstiel uses as a guide animal, one of

the first of its kind in the nation.

And while Tonto doesn't live in her bedroom, he does spend a

good deal of time in the house. "Do you see hoofprints on the

carpet?" Bernstiel asked, as the 115-pound potbellied pony

wandered around the basement of her family's busy house in

Lansdale.

The mini-horse, bred from a Shetland pony and slightly taller

than a German shepherd, is part of an experimental program of

the Guide Horse Foundation in Kittrell, N.C.

"It's one of the coolest new uses for animals for helping

people," said Sue McDonnell, an equine behavior specialist at

the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

McDonnell, who also has a miniature horse - there are 150,000

registered in the United States - said the animals are easy to

train and enjoy living with people.

A few years ago Bernstiel's mother told her to watch a

segment on the TV show 20/20 about the first guide horse,

Cuddles.

"I was shocked, but if you think about it, look at Roy Rogers

and Trigger, look at what he trained that horse to do," said

Bernstiel, whose house has so many horse knickknacks and stuffed

animals it's easy to trip over them if you're not careful.

A love of horses and ever-dwindling sight have defined

Bernstiel's life since childhood, when she was diagnosed with

Stargardt's disease, a degenerative condition. With her sight

getting worse in recent years, "I figured with the passion I had

for horses this seemed like a thing to try."

Why not a dog? Blame it on Rio, her neurotic German shepherd.

"I thought he'd get jealous," she said.

The big advantage of horses is their 35-to-40-year life

expectancy, three times that of dogs. The downside is the

upkeep: They require a (miniature) barn, hay and grain, regular

hoof clippings, and a companion horse. And forget about the lawn

- Bernstiel's has been nibbled to mud.

Janet Burleson, who started the Guide Horse Foundation, is a

longtime horse trainer who got the idea from watching her own

miniature, Twinkie, navigate her way through a flea market,

carefully avoiding electrical cords and picking the smoothest

paths.

"She was working like a guide naturally," Burleson said.

She and her husband, Don, placed their first horse with a man

in Maine in 2001. Bernstiel and a woman in Texas got the next

two. The foundation gives the horses away, relying on donations

for the $25,000 cost of training an animal for six months to a

year.

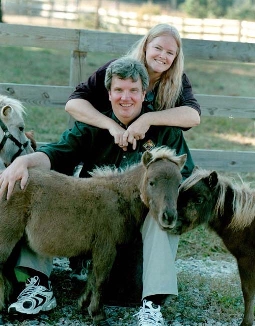

Bernstiel, chosen out of 80 applicants, worked with Tonto for

three weeks before bringing him home on Dec. 13 to join a packed

household consisting of her husband, Jim, four teenage boys

(including identical triplets), a dog and three cats.

Like a guide dog, Tonto doesn't move on his own. He responds

to 23 commands, such as right and left, or load

up and unload to get in and out of a van. "I can't

just say, 'Tonto, I want to go to Clemens,' " Bernstiel said.

On a walk around her neighborhood, he deftly negotiated

traffic, muddy sidewalks, and a construction vehicle blocking

their path. With a little nudging, he trotted across the street,

his hooves clicking on the pavement.

The duo are an endless source of fascination. A car with an

elderly couple inside slowed down to gawk. Whenever Bernstiel

goes to a store, she draws a crowd. What irks her are the

people, mostly adults, who try to pet her horse even though he

wears a sign saying that he's working.

Caring for Tonto requires more than a brushing and some

kibble. Tonto and her buddy, Kayla, live in a small barn in the

backyard that her husband and sons built. Bernstiel has to groom

and feed them, muck out the stall, and learn basic horse

psychology.

As for potty problems, well, there haven't been any so far.

Tonto is house-trained, and paws the ground when he has to go

outside. When he's inside he wears four modified baby sneakers

so he doesn't slip on floors.

Bernstiel hasn't been to any public place where Tonto was not

allowed, though one store manager waved an arm in front of her

face to see if she was really blind.

"I don't have to answer questions [about Tonto] but I will,

because I know people have never heard of this. But I always

know my rights," she said, meaning she's legally allowed to take

Tonto on planes, trains and buses, and into movie theaters and

restaurants. For now, they mostly walk to nearby stores.

While Bernstiel is smitten with her horse, some people think

the idea is strange.

"We don't know that there's a good reason [to have a guide

horse]. Dogs have worked successfully for almost a century,"

said Joanne Ritter, a spokeswoman for Guide Dogs for the Blind

in San Rafael, Calif.

Ritter sees drawbacks, such as problems gaining access to

places run by people who don't know what to make of a guide

horse, and more attention on the blind person. As for a dog's

shorter life span, she said, people's needs change over the

years, so getting a new animal every so often could be a good

thing.

Anyone who's ridden a horse can imagine the biggest potential

drawback: As prey animals, horses are easily spooked. But like

horses used in battle or to police city streets, the miniatures

are trained to "spook in place," said Burleson.

Bernstiel's animal-loving family pitches in to care for

Tonto. Her dog, however, has issues. "He's such an insecure nut,

he's pathetic," she said, making sure to pet the dog while

scratching Tonto's chest.

Bernstiel and her horse have a special bond, but that doesn't

mean she's given up her dream of having a normal-sized horse.

"People say you've gotten your horse," she said. "I say, it's

not the same thing. It's not like I'm going riding off into the

sunset on Tonto."