Tonto leads the way

By BRIAN CALLAWAY

The Intelligencer

LANSDALE - She has a knee-high stuffed toy

horse by the back door, a black and white one stabled in the

living room and a small herd of equine-figurines scattered through

her house.

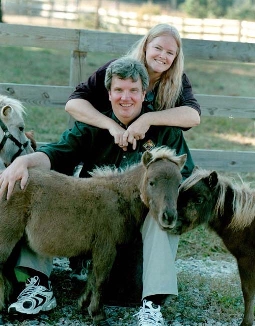

So it's no surprise that Shari Bernstiel, a self-described

"lifelong horse lover," finally decided to get a real, live one of

her own.

What is surprising is ... well, this is how she puts it:

"Look at Tonto," she said of the 3-year-old gelding. "We're not

going riding."

Tonto, a calm fellow with caramel and off-white fur and a

buttery mane, is only about 2 feet tall - larger than the stuffed

animals, but smaller than Bernstiel's German shepherd.

And while the miniature horse is meant to take her places, she

doesn't ride him.

Bernstiel is legally blind and Tonto acts like her Seeing Eye

dog - only with hooves and an occasional whinny.

Leading her with his reins through their Lansdale neighborhood

last week, he stopped before crossing intersections and briefly

guided her into a lawn to avoid a sidewalk puddle, then back on

the sidewalk, his hooves click-click-clicking their way alongside

her.

He also does stairs, elevators and car rides, has gone shopping

at places like the Montgomery Mall, and even once stayed politely

by Bernstiel's side at a movie theater.

As expected, the tiny horse's public appearances - often with

two pairs of customized baby sneakers on his hooves to give him

traction on things like linoleum floors - draw stares and more

than a few questions.

"A lot of people ask if he's stuffed," Bernstiel said. "Well,

he's walking and there's no place for batteries."

And despite the shawl he wears attached to his harness

identifying him as a guide horse that shouldn't be petted,

Bernstiel still fields requests to touch Tonto.

"With kids, I try to let them," she said. "But I can't get from

point A to point B if I stop every five steps for someone to pet

him."

Clay Lewis, who owns the North Wales News Agency, remembers

Bernstiel bringing Tonto into his store one morning.

"He was very well-behaved," Lewis said. "She'd told me she was

trying to get one, so I knew, but my customers were very much

surprised. The main topic of conversation was how do you clean up

his poop."

(For the record, Bernstiel said Tonto is "not as trained as a

dog" in that respect, but she gives him plenty of time outside

before they go somewhere.)

And while Bernstiel's never had anyone try to deny Tonto entry

- the Americans with Disabilities Act requires access for any

specially trained guide animal, not specifically dogs - she's also

heard a snide remark or two.

"Some guy commented like, 'Yeah right,' " she said. "But

(Tonto) is legitimate. He is performing a service."

Bernstiel actually has some vision. She was diagnosed as a girl

with a degenerative eye disease called Stargards, or Stargardt,

that's characterized by a reduction of central sight, though

peripheral vision generally remains.

"It's hard to describe it, because I don't know how you see,"

she said. "I think what I'm seeing is what you're seeing, only at

a farther distance."

She can't drive and doesn't really read, but can get around her

own home unassisted - though she admits she's prone to tripping

over things her sons leave lying around.

It wasn't until a couple of years ago, when she noticed her

sight getting worse, that she began to consider training with a

cane or a guide dog.

Then she heard of the Guide Horse Foundation, a North

Carolina-based group that trains horses instead of dogs to assist

visually impaired people.

According to Seeing Eye Inc., a New Jersey-based dog training

organization, about 10,000 of the nation's estimated 1 million

legally blind people use Seeing Eye dogs. In comparison, guide

horses - Seeing Eye is actually a trademark of the dog group - are

only known to be used by a handful of people nationwide as efforts

to train horses for the job are only a few years old.

"I decided to apply, never thinking I would be accepted,"

Bernstiel said.

Eventually she was. After several interviews and a trip to

North Carolina to interact with Tonto - the horse himself had

about a year of training - Bernstiel brought him home late last

year.

Since horses are herd animals, she also brought home Kayla,

another miniature horse - though an untrained one - to keep Tonto

company in his downtime.

The horses live in a small makeshift barn with a separate

fenced-in pasture in Bernstiel's back yard. The barn required a

permit, and the horses drew an inspection from the borough, but

haven't required any other special exceptions.

"They were fine," said Lansdale's health officer, Rosella

Burcin, who made the inspection. She added that she'd received no

complaints about Tonto and Kayla.

Like most guide dogs, the horses didn't cost anything, and the

upkeep isn't that expensive, with a $4 bail of hay lasting them

more than a week and a $10 bag of oats taking them through a

month.

But caring for the two horses is more difficult than for two

dogs, she said, requiring daily cleaning of their stall to keep

smells and flies away.

"It is a lot of work," said Bernstiel's 17-year-old son Andy,

who often helps with the horses. "But I don't care."

Still, why not get a guide dog?

Bernstiel said there are a couple of reasons.

In addition to her interest in horses, Bernstiel said she liked

that Tonto wouldn't be as attention-hungry as many dogs.

"I've raised five kids, a dog and three cats," the housewife

said. "I didn't want him to be emotionally needy ... and he's

happy outside."

And with Tonto's life expectancy of about 40 years, he'll last

more than twice as long as the average guide dog.

So while Bernstiel said she still might want a horse she can

actually ride someday, she likes that she can count on Tonto to be

there too.

"My vision is going to get worse, so I wanted him here now so

we could get used to each other," she said. "He's going to be the

one guide in my lifetime - that's a big plus."