Decked out in pants and a cowboy hat,

Grahmann trekked with the Burlesons, who own this 63-acre Kittrell

horse farm, and her mother to a field where she could ride. Two

young women brought out Raspberry Jam, who was a champion show horse

in his younger days, and stacked a short set of black steps at his

side. Grahmann folded her cane and handed it to her mother. With

help, she climbed the steps and mounted.

"Horses have been guiding people for centuries," Don Burleson

said. People just have to trust them, he said.

Grahmann and Raz started out walking, then they trotted along a

wooden fence. They galloped for a few steps, then lost their stride.

They hadn't found their rhythm. "She's ready to open up," said Mary

Lou Russell, anxiously watching her daughter. "I can tell."

Grahmann turned the reins to direct Raz back to where they

started and tried again. The pair did a little better this time,

loping for a short while.

"There she goes," said Janet Burleson, watching them. Sending

good vibes across the distance, she said, "Keep him going."

Grahmann and Razz traveled even farther.

"OK, buddy," said Grahmann, bringing him in. "That was good."

Looking at Grahmann's ease with Raz, you wouldn't know how far

she has come to get here. It's a journey across space and through a

tangle of emotions. Before this morning, Grahmann hadn't loped a

horse in eight years. She hasn't connected with one since 1990 when

her kindred spirit, Rebel, died. The former trophy-winning rider

traveled from southeast Texas to the Burlesons' farm to meet a

miniature horse that will this fall become her guide animal and

maybe something more.

Th rough the Burlesons, Grahmann holds hope that she'll find that

old closeness, that bond she feared was lost forever, with the mini

they trained named Pal. "Yesterday, the first time out with me, he

stopped me from continuing forward because there was a car coming,"

Grahmann said. "I kept saying, 'Forward, forward.' He was saying,

'Unh, unh.' "

Grahmann was in the eye doctor's office early this year with her

mom when Russell read her an article on the Burlesons' nonprofit

Guide Horse Foundation. Right away, Grahmann knew she had to have

one. She had considered getting a guide dog once. But she already

has four canines and feared that having another one, especially one

allowed to sleep inside, might cause jealousy and problems. Plus,

she missed bonding with horses. Ever since her Rebel died, Grahmann

felt an ache. She wondered whether it was time to risk being

vulnerable again.

With her text enlarger, Grahmann filled out the application from

the Burlesons' Web site,

www.guidehorse.com

, and waited. About a month later, the Burlesons contacted her and

planned a trip to her home to meet her.

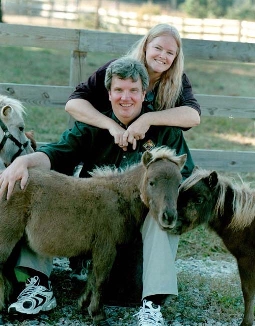

The couple are choosy about whom they trust with their horses.

Just four years ago, the Burlesons had an incredible idea -- to

successfully train a miniature horse to lead the sight-impaired .

People scoffed at the notion. But the Burlesons proved their hunch

right with an experimental project in 1999 and started a series of

firsts. Janet became the first person in the world to train a guide

horse and then trained the first guide horse to enter full-time

service with a blind person. Following their example, a handful of

people are now training guide horses in other parts of the world.

Not everyone can manage a guide horse, Don said. The person must

have a sense of navigation. It's a misconception, Don said, that a

guide animal will, without direction, take a person where he wants

to go. The new owner also must have enough yard for the horse and

its companion mini to graze and a caring heart. Grahmann passed the

first test. Now, she was in the second phase -- training.

The Burlesons, who give away the miniatures they train, paid for

Grahmann to fly to Kittrell and meet her guide horse. Grahmann knelt

down when they brought in Pal, a 90-pound, 26 -inch buckskin

gelding, and started showing him love, feeding him mints, which to

her delight he slurped. She felt a familiar tingle.

The next day, she was ready to see him again. "How are you doing,

boy?" Grahmann asked when Pal came into the Burlesons' home a little

later on a leash. He licked her fingers searching for a treat.

Grahmann and Pal had already navigated a quiet park, learning to

work together. Pal's job was to keep Grahmann safe and Grahmann's

job was to tell Pal where she wanted to go. Today, they were

tackling an urban scene. Each time they train, they'll go somewhere

different, Don said. A guide horse must be able to handle any

situation. Plus, once a horse learns a route, he said, he knows it

for good.

The group piled into Don's white Dodge Caravan heading for

Henderson. Donna sat in the front with Don. Pal stood on the back

floor -- his moving litter box -- with Don's daughter, Jennifer, and

a friend.

Don parked on a commercial strip of Garnett Street. The girls,

volunteers for the summer, laid down wooden slats. Then out padded

Pal over the makeshift ramp and onto the pavement in his white baby

shoes split to accommodate his hooves and white socks (practice for

when he walks on slick surfaces such as mall floors). Drivers craned

their necks when they saw him. Passers-by did double takes . The

teens tied a maroon bandanna around Pal's neck and laid a blanket on

his body that read "Do Not Touch. Service Animal on Duty."

"We're ready to rock and roll," Don said.

Grahmann held onto Pal's harness and reins. Janet, who has

trained horses for decades, walked next to her to help them along.

They headed down the sidewalk, past shops, by other people, through

crosswalks. After coaching Donna for a while on how to use verbal

commands such as "forward" and "wait" to communicate with Pal (they

will know 23 commands when training ends), Janet started lagging.

"We're all still here, Donna," Janet said. "We'll just stay back

a bit and let you go."

Grahmann and Pal went their way alone. The pair bumped into each

other gently at first, but then walked down the sidewalk, steered

around a tree and kept going, just the two of them together,

managing on their own.

"Good boy," Donna said with a smile, patting Pal when they

stopped near a beauty salon.

A group of youths looked on in amazement. They asked if they

could take a picture of Grahmann and Pal. The pair posed as people

from Beauty Express peeked out the door and the yellow disposable

cameras of the young men clicked.

The young men crossed the street, glancing back now and then with

wide eyes, still talking about what they saw.

An idea from Twinkie

The Burlesons didn't set out to make history. Don, who already

had a couple of minis as pets, spotted a 2-foot dwarf miniature

horse at an auction in Mount Airy. Don entered the bidding, set on

taking that mini home. "When it got to $900, Janet started nudging

me," Don said. "She said, 'What will you do with it?' She thought I

was nuts."

Don paid $950. He started treating his pet, Twinkie, like a dog,

loading him up in his minivan and taking him places like the flea

market. Don knew he was special right away. Twinkie loved people. He

was intelligent and was a natural guide. By instinct, horses are

cautious of danger. At the flea market, Don noticed how Twinkie led

him around obstacles.

One day, Don and Janet batted ideas around. The pair thought

about Twinkie and about the horses they rented in Manhattan, who

maneuvered around traffic, undaunted by blaring horns and city

noise, from the livery stable to Central Park and back to the

stable. Then Janet, a champion rider and trainer since her youth,

thought back to her early days. As a teen, she had watched a blind

woman showing a horse once. The trust and bond between them amazed

her. Could they train miniature horses to lead the blind?

"We were laughed at and got everything from skepticism to

amazement when we first started," Don said. "Some people said,

'You'll never be able to housebreak a horse.' A lot of people didn't

understand horses. They had already been guiding people at the turn

of the century. People back then understood."

They set to work on Twinkie. Don, who has a degree in

experimental psychology, had the know-how in memory theory and

conditioning. Janet, whom Don calls a horse whisperer, had the

experience in training around behavior challenges and getting the

response she wanted.

Janet, with Don helping out, devoted hundreds of hours,

housebreaking Twinkie, teaching him to ride an elevator, navigate in

traffic, spook in place (remain calm in noise and chaos), practice

intelligent disobedience. If the blind person commands the horse to

go and there's danger, the horse has to have the smarts to stop

anyway and protect his charge. They were training with him in

Crabtree Valley Mall in Raleigh one day when someone at a local

television station spotted them.

That set off the national sensation. The couple have been

featured on everything from "Ripley's Believe It Or Not!" and

"20/20" to the children's magazine Highlights and the "Today" show.

They never planned to put the guide horses into practice. But in

2000, Dan Shaw of Maine heard a woman on TV talk about the guide

horse she had trained. Shaw, who had considered guide dogs, made up

his mind that he needed one. He found the Burlesons' number and

called.

"He pestered us incessantly," Don said. "We had never planned to

place horses. We just wanted to see if it could be done."

As word spread, donations poured in to buy the minis from

breeders. Children mailed their allowances. Celebrities sent

anonymous monetary gifts. Stores donated products. When they don't

get donations, Don, who has written more than 30 technical computer

database books, and Janet, a Web design consultant, pay for

everything themselves.

Novelist Patricia Cornwell, who asked to be blindfolded and

guided around with a Burleson mini, donated several miniatures,

including Cuddles, the one they trained for Shaw. Twinkie, who had

the necessary intelligence and excellent health, did not have the

agility to be an official guide horse. Just one or two in 100

miniatures have what it takes.

"Cuddles has changed every aspect of Dan's life," Don said. "He

went from being introverted to bold and outgoing. It's gratifying to

see how animals can change owner s' lives. After Dan, the phone was

ringing off the hook with blind people from all over the country. We

had blind people crying on the phone, trying to bribe us, cajole us.

There's lots of need out there."

After Shaw, training guide horses became a mission for the

Burlesons. They give their time for free. Their foundation pays for

the guide horse training, follow-up visits, trips for the

sight-impaired person to practice with the horse. The recipient of

their gift pays nothing. For the Burlesons, the reward is watching

the guide horse and blind person grow together. The Burlesons will

place two miniature horses this year, one with Grahmann and one with

a woman in Pennsylvania. They're in no rush to place more. Building

trust with the horses and with the blind handlers takes time. The

Burlesons are training horses who will be entrusted with someone's

life. They know what a weighty duty that is. They've pledged to

nurture those relationships for the rest of their lives.

Lifelong love of horses

Sitting in the Burlesons' living room, decorated with horse

pillows, golden horse figurines and framed pictures of mares on the

walls , Donna talked about how she got here. She fell for horses the

first time her parents took her to ride a pony around a circle in

downtown Houston. "Ever since I could say horse," Grahmann said, "I

wanted one."

She got Rebel, a bay quarter horse, in 1977. Her mother remembers

when Grahmann spotted him.

"He was in a stall and had his head down," she said. "Just when

Donna got to the stall, he raised it. He had the most gorgeous eyes.

She gasped."

The next year, Donna and Rebel won the state championship in pole

bending. Together, they've placed in a world youth competition in

the stake race and in the Quarter Horse Congress in trail, pole

bending, barrels and western riding. Along with sharing moments of

glory, Grahmann was with Rebel at one of her worst moments too.

"I was sitting on Rebel at a horse show looking at lights on the

ceiling waiting for my turn," said Grahmann, who was in her early

20s. "The light turned orangey-red. My eye was hemorrhaging."

Grahmann was losing her sight to diabetic retinopathy, an eye

disease caused by complications from diabetes. A specialist wasn't

able to save her right eye. A letter came from a doctor telling her

that one day she would be totally blind. "I knew it would happen one

day," she said. "But seeing it in black and white was hard. It shook

me up."

By 1989, Grahmann was legally blind in her left eye too. She kept

riding. Rebel was her vision. Grahmann and Rebel knew every move the

other would make. He adjusted for her movements in the saddle. They

even ran poles together. Don compared it to skiing slalom. Grahmann

felt safe in any situation. "I could pretty much just sit there,"

she said. "I knew if I was starting to slip out of the saddle, he'd

slow down. I trusted him with my life."

When Rebel was struck by lightning the next year and died,

Grahmann felt empty. "I knew I'd never have another connection like

that," she said. "I had one other horse after Rebel and it wasn't

the same."

She struggled to manage on her own. In unfamiliar places, she

grabbed her husband's elbow or her mom's. When her husband dropped

her off at the grocery store, Donna bravely entered but trembled

inside. She cringed when she knocked over orange cones and displays

in the aisles. She lost hope of ever finding another horse with whom

she could have that special bond. Rebel would guide her around the

low limbs and trees on her property. She didn't know what a new

horse would do.

"I didn't trust them or myself," she said.

Grahmann still mourns Rebel. She has a painting of the two of

them in her bedroom. The trophies they won together are around her

house. "I don't think I'll ever get over losing him," she said. "He

was like my child."

But maybe she can make room in her heart for one more. With

Rebel, it was love at first sight. With Pal, she could make out the

length of his body, but couldn't tell what color his mane and tail

were. It didn't matter. Instinct told her he was special. Grahmann

knows that, like Rebel, he can help her feel independent and free.

"I'm just ready to have another animal like that in my life," she

said.

Learning to trust

On her last day in North Carolina, Grahmann rode some more on Raz.

This time, they loped easily along the fence. Stoked, Grahmann went

inside to start another day with Pal. When he trod in, she greeted

him like an old friend. Grahmann blew gently near his nostrils.

"When two horses meet, they blow puffs of air at each other," Don

said.

She fed him a piece of ice from her glass of water, holding it in

her hand and letting him lick it through her fingers until they

dripped. "I was amazed yesterday," Grahmann said, "at how he was

leading me around trees. Once I got close to them, I could see them

but I didn't want to give him commands. I wanted to see if he could

do it and he did."

It's like Rebel, Russell said. He would accommodate Donna and

keep her safe. She slipped once from his back when he made a sharp

turn running polls. "You've never seen a horse shake so bad,"

Russell said. "He didn't stop shaking until he could put his head on

Donna."

Russell thinks that Donna and Pal will forge that kind of

connection. There are already signs -- the way Grahmann gleams when

he enters, the ease with which Pal took to her.

"I think it will develop to that," Grahmann said. "I already got

him in my heart."

The day's lessons started at PETsMART. "OK," Donna said,

confidently, holding onto Pal's reins, "which way is the store?"

"Forward, forward," she told Pal, clicking her teeth.

"When they complete training," Janet said. "Donna will be able to

just say, 'Find the door.' "

Inside, people gawked. A little girl tugged on her mother's arm.

"Mommy, it's a pony," she said.

Pal never faltered. Together, Grahmann and Pal navigated the

store's aisles, past the bird cages and aquariums. Down each row

were different obstacles. A doggie bed sat in the middle of one; a

tall ladder was at the center of another. Together, they made it

around each hurdle. Pal stayed still at a hefty stack of dog food

that left just a narrow passageway for the two of them. Grahmann

nudged him with her knee to encourage him forward. Reluctantly, he

continued. Grahmann bumped her arm on the edge of one aisle.

"He was telling you it was too tight," Janet said.

By the time they go home together in October, they will know each

other's language. On the way back to the van, a car stopped to allow

them to pass in front of them. Pal chose the safest way -- behind

it. This time, Grahmann followed him.

The Burlesons and Pal took Grahmann and her mother to the

airport. The pair practiced on moving sidewalks and elevators,

maneuvering through crowds before it was time to part.

Grahmann checked in at the gate. She won't see Pal again for a

while. Grahmann will return for her last training session -- even

more intense work of learning how to use Pal safely and mastering

techniques -- right before she takes him home. Guide horses have to

be 100 percent proficient at traffic training before the Burlesons

turn them over to their blind handlers. A misstep, Don said, could

mean someone's life. They will work with Pal while Grahmann is gone

to make sure he's ready. The trust must be absolute.

"A guide horse and a blind person develop a symbiotic

relationship," Don said. "They become one."

The group headed to the place where they would say goodbye.

Grahmann knelt and rubbed Pal's caramel-colored coat. Pal warmed to

her attention.

"I hope he remembers me when I get back," she said.

She and Russell headed toward security. Grahmann took one final

look, waving and beaming until she disappeared from sight.