|

|

Ridgewood Homeowners Assn. v. Mignacca

Rhode Island Superior Court

2001 WL 873004

July 13, 2001

Summary of Opinion

Plaintiff homeowners association brought a lawsuit for a court order

that defendant Mignacca must not keep their miniature horse Sonny on

their 4 acre property. The plaintiffs claim that keeping the miniature

horse violates both town zoning ordinances and restrictive covenants of

the subdivision in which the defendants lived.

In this superbly-written, urbane, and humane opinion, the trial court

denies the association’s claims. The judge found that the zoning

ordinance does not prohibit keeping Sonny and that properly interpreted

the restrictive covenants do not prohibit keeping pets such as Sonny.

Accordingly, the court denies relief to the plaintiffs and permits Sonny

to remain on the Mignacca’s property.

Text of Opinion

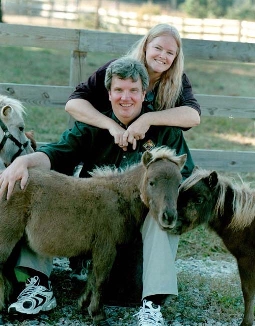

This case presents the Court with the question of whether Kathy and

David Mignacca and their four minor children may lawfully keep Sonny,

their miniature horse, at the family's residence in the Ridgewood

subdivision of western Cranston. The Mignacca family, the Ridgewood

Homeowners Association and those property owners and residents of the

Ridgewood subdivision who contend the Mignaccas cannot lawfully harbor

Sonny have brought the controversy before the Providence County Superior

Court by way of two paths.

On April 11, 2001, the Zoning Board of Review of the City of

Cranston, after hearing from the Mignaccas, Rena Dresseler, the

president of the Ridgewood Homeowners Association and a vigorous

opponent of Sonny's residing in Ridgewood, as well as other persons

supportive of and opposed to the Mignaccas' position, granted the

Mignaccas' petition for a variance and allowed them to keep Sonny on

their nearly four acre lot, subject to certain conditions. From that

decision, the Ridgewood Homeowners Association, Ms. Dresseler and others

claimed an appeal to this Court. On the 22nd day of May, 2001, the

Ridgewood Homeowners Association, Rena Dresseler and other individual

homeowners from Ridgewood went on the offensive against the Mignaccas

and Sonny, and filed a verified complaint seeking injunctive relief to

bar the Mignaccas from keeping Sonny on their property and from erecting

and maintaining a shed to shelter the miniature horse, the plaintiffs'

contention in this suit being that restrictive deed covenants prohibited

Sonny from being kept in Ridgewood. A temporary restraining order was

issued by this Court May 23, 2001 enjoining the Mignaccas from keeping

Sonny on their property until the matter was finally adjudicated on the

merits. A counterclaim challenging the keeping of any animals by the

plaintiffs, other than cats and dogs, was filed by the Mignaccas on July

11, 2001.

On June 27, 2001, the parties and their attorneys appeared in this

court prepared to try the equitable matter, not just on the question of

a preliminary injunction but on the merits, pursuant to Rule 65 of the

Rhode Island Rules of Civil Procedure. On July 2, 2001, the zoning case

and the equity case were consolidated for trial on the merits, with the

attorneys for the Mignaccas, the Ridgewood Homeowners Association and

individual members of the association who have joined in the litigation,

and the Cranston Zoning Board of Review, all concurring that this was

the appropriate way to proceed. It is well established, of course, that

equity seeks to avoid a multiplicity of suits and that R.I.G.L. §

8-13-2, the legislative grant of equitable powers to the Rhode Island

Superior Court, provides for consolidation of all matters arising out of

the same occurrence or transaction. See also Rule 42, Super. R. Civ. P.

This Court, sitting without a jury, took testimony during a number of

half-day sessions, commencing on June 27, 2001 and ending on July 12,

2001. The principal facts of significance are not in dispute; and

indeed, counsel for the Mignaccas and for the Association have

stipulated to a number of facts.

Christian Mignacca, the nine-year old son of Kathy and David Mignacca,

was the first to testify in this matter, and I find his testimony to be

credible and trustworthy. Christian answered all questions put to him by

counsel and the Court in a forthright and articulate manner. He spoke of

his involvement with the training of Sonny during Sonny's stay of

approximately thirty days at his home before the issuance of the

temporary restraining order; and he discussed the behavior of the

miniature horse both while it is housed on the Mignacca property and

when it participates in horse shows and competitions at venues designed

for that purpose. Christian explained that he has won a number of

ribbons while competing with Sonny against other miniature horses and

their masters. While Kathy Mignacca and Christian's sister, Nicole, also

participate with Sonny in such contests, it is clear that Christain's

involvement with the training and showing of the little horse is

significant. Christian also discussed his physical limitations resulting

from bacterial meningitis when he was two.

From Kathy Mignacca, whom I also find to be a credible witness,

Christian's activities with Sonny were confirmed, and the Court was also

told that Christian's involvement with Sonny and the miniature horse

competitions has been a great source of enjoyment and satisfaction for

the boy, and indeed has been helpful for his confidence and self-esteem,

given the fact that his early childhood bout with the often fatal

disease of bacterial meningitis has left Christian with scarring over

much of his body, including his face and arms, and with weakened legs

that require him to wear braces frequently. His weakened limbs preclude

him from participating in other competitive sports appropriate for his

age, such as baseball, soccer or football, and he finds the delights and

challenges of competition in the horse shows he enters with Sonny.

Regarding Sonny himself, the Court learned of his behavior, habits

and growth potential from Christian and Kathy Mignacca, and had the

opportunity to observe Sonny on the Mignacca property during a view on

July 6, 2001. Sonny's shoulders will never be higher than 3 feet from

the ground and his weight will never exceed 150 pounds. The animal, by

all descriptions, as well as by the Court's view on July 6, is gentle,

amiable and not high strung or vicious in the least. His stature and

weight will never reach that of a Great Dane, a Bull Mastiff, or a Saint

Bernard; and it is unlikely that any training could make him into a

guard or attack animal along the lines of a Doberman Pincher, a German

Shepherd or a Pit Bull. Indeed, the popular name for this

animal--"miniature horse"--is an apt one. When Shakespeare's Richard III

cried out to his deity and the fates to supply him with a horse in

return for his kingdom, if Sonny (or one of his ancestors) had appeared

from the underbrush into the clearing, the distraught king surely would

have uttered an Anglo-Saxon expletive that would make an Elizabethan

audience blush and then fallen on his sword. [FN1] Alas, Sonny the

miniature horse cannot be ridden nor used to pull a plow through a

field.

FN1. "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!" from William

Shakespeare, King Richard III, Act V, Scene 4.

The defendants also presented Anthony DelFarno, a Ridgewood neighbor,

who testified that for nearly two years between 1998 and 2000, his

family kept a miniature horse on his property, and that at least one

board member, Laurie Biern, had seen the horse, Pogo. According to Mr.

DelFarno, Ms. Biern liked the little animal, and he never received any

complaint from the board of directors or any other person regarding his

keeping the animal. He made no attempt to conceal the fact Pogo was on

his premises, and the miniature horse could be viewed from the street.

In order to properly care for the horse, Mr. DelFarno converted a

portion of his 15 x 25 foot shed into an appropriate place for Pogo. At

some point, he received a letter signed by Ms. Dressler in her capacity

as President of the Ridgewood Homeowners Association telling him that

the shed was in violation of the restrictive covenant pertaining to the

building of such structures, apparently, Section 6, which provides,

among other things, that "no structure ..., shack ... or other

outbuilding shall be used, placed, erected or constructed on any lot at

any time either temporarily or permanently." Upon receiving the letter,

Mr. DelFarno said that he called each member of the board, and none of

them had any information or even noticed that there was any problem with

his shed. As his testimony was uncontradicted, the only conclusion to be

drawn by the Court is that Ms. Dressler, without advising other board

members, took it upon herself to tell Mr. DelFarno that his shed was in

violation of the restrictive covenant. For his part, Mr. DelFarno

advised Ms. Dressler, and apparently anyone else with whom he spoke,

that he would take his shed down only if the other cabanas, sheds, and

outbuildings scattered throughout the subdivision were also removed by

their owners. Mr. DelFarno opined that the homeowners association

enforced its covenants arbitrarily.

In their case seeking equitable relief, the plaintiffs called no

witnesses to the stand, though Rena Dresseler testified when called by

the Mignaccas. Ms. Dresseler testified that she had occasionally heard

Sonny neigh while she was on her property some three or four hundred

feet away from where the Mignaccas keep Sonny in a fenced enclosure. It

is difficult to believe that Sonny could be heard from that distance, as

his neigh, such as it is, is more akin to a cat's meow and apparently

does not occur very frequently according to Kathy Mignacca. When the

group of approximately fifteen people who went on the Court's view

approached Sonny in his enclosure, the sound made by the footfalls was

noticeable and at least three persons in the entourage carried large

television cameras on their shoulders. This was probably not a sight

that Sonny had encountered in the past, yet his reaction was one of

silent indifference as he continued his equine ruminations. Counsel for

the Association was invited by the Court to attempt to make Sonny emit a

sound, but the invitation was declined. Kathy Mignacca declared that the

horse would neigh usually when presented with food. In the presence of

those who were attending the view, Kathy Mignacca entered the enclosure

and offered food to Sonny, who obliged with a neigh--of the feline meow

variety--which could barely be heard 20 feet away.

During her testimony, Ms. Dresseler also disclosed that at some point

in the past, she had kept a 4 foot boa constrictor as a pet and was

presently keeping on her premises three iguana lizards, and three or

more stray cats that she regularly fed and who stayed under her outside

deck. Additionally, she has on her premises two parrots.

During the view, Ms. Dresseler's residence was also visited by the

Court and counsel for the Mignaccas and the Association. From her deck,

one can look across the adjoining backyard and pool of the Nardolillo

family and get a glimpse of portions of the Mignaccas' garages and the

top of a slide that has been placed near their swimming pool. The

Mignacca pool and house cannot be seen, nor can the enclosure and shed

in which Sonny is kept. Sonny himself, could not be seen, but Ms.

Dresseler ascribed that to the fact that a pile of dirt resulting from

excavation in the Nardolillo's backyard obscured the view. As the fact

finder, I conclude that even without the dirt in the way, the stands of

trees, shrubs, bushes and plants on three parcels of land would make a

view of Sonny difficult, if not impossible; and if one did chance to

catch a glimpse of Sonny from the Dresseler deck, the miniature horse

would appear as a tiny denizen of Lilliput, the island Gulliver visited

in his famous travels. Sonny, it should be noted, is kept behind the

Mignacca house and to the rear of their property, and cannot be observed

readily, if at all, from the street. The Mignaccas have created for

themselves, through planting and landscaping, a park-like environment.

All the houses in Ridgewood are what might be termed, by way of

understatement, upscale and lavish. Ridgewood, in short, is a verdant

and secluded enclave for some members of Rhode Island's economic

aristocracy.

At several times during the course of these proceedings, counsel for

Ridgewood and Ms. Dresseler argued that David and Kathy Mignacca were

exploiting the afflictions of their son, Christian, in order to gain the

favor of the Court, as well as popular sympathy by way of media

manipulation, for whatever good that might gain them. The genesis of

this contention apparently is Ms. Dresseler, who obliquely opined during

her testimony at the zoning hearing that the Mignaccas were seeking to

use the condition of Christian to gain the favor of the zoning board.

(Tr. 22). Kathy Mignacca testified in this proceeding that she and Ms.

Dresseler had a confrontation about this accusation after the Zoning

Board of Appeals had taken testimony and rendered its decision. These

suggestions by Ms. Dresseler and her lead attorney on this point are

reckless, mean-spirited and not supported by one iota of evidence. On

the contrary, the transcript of the April 11, 2001 zoning hearing

demonstrates that from the outset Kathy Mignacca has been candid and

forthright about the salubrious affect playing and working with Sonny

could have on Christian. (Tr. 9, 13-14). This Court takes judicial

notice of the emotional and physical well being animals kept as pets

often bring to their human companions [FN2].

FN2. A number of scientific studies have confirmed what any

casual observer of pets interacting with humans should know. See,

e.g. Alan M. Schoen, Kindred Spirits: How the Remarkable Bond

Between Humans and Animals Can Change the Way We Live (2001).

But, while relevant, it is not the physical and psychological

challenges that Christian confronts as a result of his bout with

bacterial meningitis that govern the outcome of this case. The paramount

concerns of this Court in resolving the controversy are the ordinances

of the City of Cranston, the decisional law of the Rhode Island Supreme

Court respecting restrictive covenants, and the principles and maxims of

equity. Logic suggests that the first point of examination be the

Cranston City Code, for if Sonny's residing with the Mignaccas is

prohibited by the ordinances of Cranston, then an examination of the

restrictive covenants is pointless.

Land Use and Zoning Ordinances in Cranston

On April 11, 2001, the Mignaccas pressed their request pursuant to §§

30-8 and 30-28 of the Cranston zoning ordinances before the Zoning Board

of Appeal. Section 30-28 provides for a procedure to obtain variances

and § 30-8 is a schedule of uses. Apparently the Mignaccas were

concerned about permitted uses in an A-80 zone, which allows not only

single-family residences on large lots but provides for the "raising and

keeping of animals on not less than ten acres." The Board took testimony

for and against the application, and learned, among other things, that

Sonny would be kept in a 10 foot by 12 foot shed if the Board so

permitted, would be spending his days in an enclosure bordered by a 500

foot fence that in turn was within the Mignaccas fenced-in property, and

that Sonny required approximately one-half acre for his exercise. The

Zoning Board of Review granted the request of the Mignaccas to keep

Sonny on their property along with the 10 foot by 12 foot shed, subject

to certain conditions; and the Board was specific in its decision that

they had factored in the concerns of Kathy Mignacca for the well being

of Christian. While the Board of Review did not fully explicate its

decision, they granted a dimensional variance from the 10 acre

regulation relative to "raising and keeping ... animals", implicitly

concluding that Christian would experience more than a "mere

inconvenience." (R.I.G.L. § 45-24-41(d)(2)). One condition imposed by

the Board was that the horse could remain "as long as [Christian] ... is

living there or no more than nine years whichever comes first.."

A review of Cranston's ordinances reveals, however, that the

Mignaccas are able to keep Sonny on their property without repairing to

the Board of Appeals for a variance, as § 4-2.1 of the City Code

provides that horses may be kept in different sections of the city so

long as sufficient acreage is available. Section 4-2.1 entitled "Keeping

animals in certain districts prohibited," a certified copy of which was

placed in evidence by the Court, provides, in pertinent part:

No person shall keep any horse within any closely built-up

residential area unless he shall have available, either through

ownership or lease, at least 20,000 square feet of pasture area.

As an acre contains 43,560 square feet, and the Mignaccas have a four

acre house lot, there does not appear to be any question but that they

can keep a miniature horse on their property. The word "pasture" of

course refers to grass growing on land that has not been tilled for

cultivation and which is available for an animal to graze upon.

The City Council of Cranston was acting within powers delegated to it

by the legislature when it passed § 4-2.1 respecting the keeping of a

horse in a built-up residential area. R.I.G.L. 23-19.2-1 provides, in

pertinent part:

The councils of the several cities and towns may make such rules

and regulations as they deem necessary to regulate and control the

construction, location and maintenance of all places for keeping

animals ...

No authority has been presented to this Court that in any way

suggests that either the zoning ordinances of the City of Cranston, the

Cranston comprehensive plan or the statutory enabling legislation

nullify the controlling force of § 4-2.1.

Restrictive Covenants

I turn now to an examination of the restrictive covenants at issue in

this controversy. The document containing all restrictive covenants

pertaining to the parcels located in Ridgewood Estates is Exhibit A in

the consolidated action.

Restriction 8, titled "Livestock and Poultry ", provides in its

entirety:

No animals, livestock or poultry of any kind shall be raised,

bred, or kept on any lot, except that two (2) dogs and/or two (2)

cats may be kept provided that they are not kept, bred or maintained

for any commercial purpose. No kennels or other structure for the

keeping of such pet shall be maintained on the premises.

The plaintiffs also rely on Restrictive Covenant 5, which defines

nuisances; and after amending their complaint, the plaintiffs sought to

demonstrate that the Mignaccas used offensive construction or lawn

machinery and recreational vehicles on their land, in addition to

keeping Sonny. Restrictive Covenant 5, titled "Nuisances ", provided in

its entirety:

No professional, trade, business or commercial enterprise of

whatsoever nature may be conducted or operated on the granted

premises. No substance, thing or material shall be kept of used on

any lot which will emit foul or obnoxious odors or that will cause

any noise that will or might disturb the peace, quiet, comfort or

serenity of the occupants of the surrounding property.

It is necessary for this Court to determine the intended scope of

Restrictive Covenant 8. Rena Dresseler and the Ridgewood Homeowners

Association argue strenuously that Sonny should be placed under the

category of "livestock" and therefore cannot be kept on the Mignaccas'

Ridgewood property. Our legislature has seen fit to define the term

"livestock" in contradistinction to the word "pet" in an effort to

categorize different members of the animal kingdom. In R.I.G.L.

4-13-1.2(5), we find the following definition of livestock:

"Livestock" means domesticated animals which are commonly held in

moderate contact with humans which include, but are not limited to,

cattle, bison, equines, sheep, goats, llamas, and swine.

R.I.G.L. 4-13-1.1(8) favors us with us a definition of pets:

"Pets" mean domesticated animals kept in close contact with

humans, which include, but may not be limited to dogs, cats,

ferrets, equines, llamas, goats, sheep, and swine.

It appears, then, that the legislature recognized that horses--as

well as some other animals such as, llamas, goats, and even swine--can

be categorized as either livestock or pets, the different labels to be

applied according to the degree of contact the animal has with humans.

In the instant matter, it is clear that Christian, and some other

members of his family, have close contact with Sonny and treat him as a

pet as they engage in almost daily routines with him involving feeding,

training, grooming, playing and showing in horse competitions.

In addition to their contention that Sonny must be placed under the

rubric "livestock", the plaintiffs argue that this restrictive covenant

must be read to bar the keeping of any animals except two dogs and/or

two cats per lot on property situated in Ridgewood.

In seeking to determine the intent of the drafter of this covenant,

the principles of statutory construction as enunciated by the Rhode

Island Supreme Court and other authorities provide a guide. One rule of

construction is that "general terms be construed as limited by more

specific terms." Montaquila v. St. Cyr, 433 A.2d 206, 214 (1981). It

appears that the all-inclusive term "animal" has been limited by the

words used in the title of the covenant, "Livestock and Poultry," and

further limited by the use of those same words following immediately

upon the use of the word "animal" in the text. Also apposite is the

"principle of noscitur a sociis, that the meaning of one word can become

clear by reference to other words associated with it in the statute ..."

Berthiaume v. School Com. of Woonsocket, 121 R.I. 243, 248 (1979). [FN3]

FN3. A scholar of the rules of interpretation provides useful

instruction: "Noscitur a sociis ", the most sonorous of the canons

of construction, is also the most obscure. It is often confused with

ejusdem generis even by those who should know better. Whereas

ejusdem generis tells us how to find items outside the list

expressed in the statute, noscitur a sociis tells us how the list

gives meaning to the items within it. Michael Sinclair, A Guide to

Statutory Interpretation (2000).

Naturally, to resolve ambiguities or a lack of clarity of intent, the

restrictive covenant must be read in its entirety and harmonized with

every other covenant in the deed. The plaintiffs pled that they

perceived a breach of the livestock and poultry provision (Restrictive

Covenant 8) and also pled that the Mignaccas were in violation of the

nuisance provision (Restrictive Covenant 5) in keeping their horse and

shed on their land. Not one shred of evidence was produced suggesting

that either Sonny or the 10 foot by 12 foot shed produced any sort of

nuisance, either by way of emitting noxious odors, disturbing the peace

or by creating an eyesore. This Court can judicially note that a greater

noise level than could ever be generated by Sonny would result from any

number of usual Ridgewood activities, such as backyard barbecues,

teenager pool parties, barking dogs and the chirping of crickets after

dusk.

I conclude that the intent of the drafter of Restrictive Covenant 8

was to provide the residents and potential residents of the Ridgewood

development from having a neighbor or neighbors engage in the business

of keeping and raising animals in a farm-like setting for commercial

purposes, i.e., the raising of chickens for their eggs and meat, the

raising of cattle for dairy products, the maintaining of a horse stable

for riding lessons and to make a profit by boarding other people's

horses, etc.

Additionally, the covenant is unclear as to whether such animals as

are barred by Restrictive Covenant 8 are precluded from only the outside

of a dwelling place or whether they are barred from the inside as well.

The lead individual plaintiff, Rena Dresseler, asserts a right to keep

parrots, lizards and snakes within her house, claiming that Restrictive

Covenant 8 applies only to land outside the house. This viewpoint is

mistaken and not supported by the language of the covenant. At best, the

covenant is ambiguous as to the scope of its application, as the use of

the words "lot" and "premises" within the covenant do not by and of

themselves bespeak of any distinction between the area situated inside

the house and that located outside. Controlling authority of our Supreme

Court directs how this ambiguity is to be resolved:

... the general rule concerning restrictive covenants is that

they are to be construed strictly so as to favor an unrestricted use

of property, are not to be extended by implication, and if there is

ambiguity, it is to be resolved in favor of an unrestricted use.

Emma v. Silvestri, 101 R.I. 749, 751 (1967).

Following Emma, this Court concludes as a matter of law that such

animals as may be kept at the residences in Ridgewood may be kept either

inside or outside the actual dwelling in the discretion of the owners.

This parsing of the language of the restrictive covenants and an

examination of the entire document creating these deed restrictions is

consonant with the law governing judicial scrutiny of such documents, as

found in Gregory v. State, Dept. of Mental Health, Retardation and

Hospitals, 495 A.2d 997 (R.I.1985) and DeWolf v.. Usher Cove Corp., 721

F.Supp. 1518 (D.R.I.1989). Of particular concern to this justice is the

mandate that "restrictive covenants are to be strictly construed in

favor of the free alienability of land while still respecting the

purposes for which the restriction was established." Hanley v. Misischi,

111 R.I. 233, 238 (1973). Also, because of the different fact patterns

that emerge in each dispute regarding land use and plats or subdivisions

subject to restrictive covenants, these controversies must be decided on

a case-by-case basis. Hanley, 111 R. I., at 238. And as former Chief

Judge Pettine wrote in DeWolf, after surveying Rhode Island law,

restrictive covenants should generally be viewed "as creating a valid

contractual relationship so long as they are not contrary to public

policy or law or are not unreasonably or arbitrarily enforced." DeWolf,

721 F.Supp., at 1528.

In addition to containing the ambiguities already discussed above,

the restrictive covenants involved in this matter, especially

Restrictive Covenant 6, "Temporary Structures " and 8, "Livestock and

Poultry ", have been enforced arbitrarily or not at all. Rebuttal

witnesses called by the plaintiff testified to the effect that the

original developer went bankrupt around 1994 and from that time forward

there was no mechanism for the enforcement of the covenants. This meant

that during this time people could build on their property and keep

animals in violation of the restrictive covenants. Indeed, during the

view, freestanding garages, as well as in one case a garage built under

a house, all in contravention of the restrictive covenants, were

observed, as was a driveway built without regard to the specifications

found in the covenant. Testimony was presented by witnesses for both the

plaintiff and the defendant that indicated the existence of sheds and

cabanas throughout the plat in violation of the covenants, at least

according to the perception of the person giving the testimony. None of

these covenant "violations" seemed to detract in any way from the

manicured and upscale ambiance of the neighborhood. However, the

rebuttal witnesses were mistaken in their declarations that as residents

of Ridgewood they were powerless to enforce any perceived violations of

the covenants until the plaintiff Homeowners' Association was created

around 1998. As the Rhode Island Supreme Court said in Houlihan v.

Zoning Board of New Shoreham, 738 A.2d 536, 538 (1999):

This court has long recognized that when recorded plat-lot

restrictions appear intended to provide for a uniform development and

use of platted subdivision lots, any one of the plat-lot owners may seek

judicial assistance to compel compliance of another lot owner with the

restrictive covenants.

In effect, between 1994 and 1998 there was a holiday in Ridgewood

from the mandates of all the restrictive covenants. While an expert real

estate broker and appraiser, one Donald Coletti, called by the

plaintiffs, testified as to the efficacy of restrictive covenants in

preserving the character of a neighborhood, he had nothing to say about

the deleterious affects of any specific violations on Ridgewood. He

further testified that he had participated in the transfer of the

Mignacca home from its former owners, and that he from time to time

engaged in the sale of other homes in this section of Cranston. At the

time he testified, he was trying to sell a home in Ridgewood Estates and

had not been able to bring about the sale as quickly as he would have

liked; but none of this was attributed to the Mignaccas and their

keeping of Sonny on their property, or to any other violation by any

person regarding the restrictive covenants.

Not only was there a four year hiatus in the enforcement of these

restrictions, though no resident of Ridgewood was obliged to stay his or

her actions regarding any perceived violation, it is clear that the

president of the association has kept animals on her property, the

existence of which were known to other members of the association. As

noted above, the DelFarno miniature horse, Pogo, was also known to at

least one member of the board of directors of the association and

presumably known to many other residents of the subdivision, as the

animal was observable from the street. The board member, Laurie Biern,

testified that she believed the horse was there for only three months

and that the reason she did not report it was that she thought the

DelFarnos were simply taking care of the horse for a short period of

time as an act of mercy because the horse, according to Ms. Biern, was

undernourished when the DelFarnos acquired it. She described herself as

an animal lover who regularly takes in stray animals, including "wild

cats" in order to nurse them to health.

This Court concludes that the restrictive covenant relative to

livestock and poultry is now being applied arbitrarily to the Mignaccas.

There is no exception in Restrictive Covenant 8 that provides for

miniature horses to be kept so long as they are being nursed to health.

In fact, as Rene Dressler testified, there are no written rules,

regulations, or guidelines of any type or description that contain

criteria as to when an exception may be granted relative to the

enforcement of Restrictive Covenants 5, 6 and 8. As I indicated above,

the intent of the drafters of the restrictive covenants was not to bar a

pet such as Sonny, but rather to prohibit cattle and horse farms,

chicken coops and the like. Nonetheless, another factor in this Court's

decision is the arbitrary enforcement, or non-enforcement, of the

covenants.

Equity

The keeping of animals other than dogs and cats by Rena Dresseler,

the regular harboring of animals by Ms. Biern, including a litter of

"wild cats", the keeping of more than two dogs or two cats by other

residents of Ridgewood, and the failure of any action to be taken

against the DelFarnos and "Pogo" by the plaintiffs, not only show an

arbitrary enforcement of Restrictive Covenant 8 but place in front of

the plaintiffs an insurmountable barrier regarding the equitable maxim,

"He (or she) who seeks equity must do equity." This maxim is not to be

confused with the clean hands doctrine. [FN4] The fundamental equitable

maxim that I rely upon declares, in effect, that one who seeks to invoke

the equitable and extraordinary injunctive power of the court relative

to a claimed covenant violation cannot himself or herself be in

violation of that same restriction, or have ignored other similar

violations by other persons. It would be manifestly unfair for members

of the association or other residents of Ridgewood to keep snakes or

parrots or three dogs while denying Christian and the Mignaccas a right

to keep their miniature pet horse Sonny. Moreover, the plaintiffs have

not proved harm--let alone irreparable harm--to their respective

properties or to any rights they enjoy. The plaintiffs would like this

Court to believe that without injunctive relief the Mignaccas' property

will have the appearance of a cross between Old MacDonald's Farm and

Noah's Ark situated on Tobacco Road, but nothing in evidence suggests

this.

FN4. See, e. g. John Pomeroy, II Trestise in Equity

Jurisprudence, (1941 ed.) Pomeroy declared this maxim to be "the

foundation of all equity", p. 51, and treated it in a separate

section, Section III, from that in which he examined "clean hands."

Section IV.

"The decision to grant or deny an injunction is a matter within the

sound discretion of the trial court." Paramount Office Supply Co. v.

D.A. MacIsaac, Inc., 524 A.2d 1099, 1101 (R.I.1987). Putting aside for

the moment my analysis of the restrictive covenants that appears above,

the plaintiffs have not produced any evidence whatsoever that indicates

that Sonny and the shed he uses constitute a nuisance. In my view, it is

doubtful that he can be heard beyond the boundaries of the Mignacca

lots, and if his gentle whinny happens to ride a breeze on to some

neighbor's property the sound will be barely audible, and certainly not

anywhere as loud as the barking of even a small dog. There was no

testimony as to any odors coming from Sonny or the manure he generates;

and this is not surprising as the horse during the view was immaculately

groomed; and Ms. Mignacca testified that the manure is collected

regularly by the family and kept in sealed bins (which were displayed on

the view) until its removal from the property. No evidence was produced

indicating that Sonny's presence will in any way inhibit neighbors from

the free and untrammeled use of their own property, nor will his

presence diminish property values. Balancing the equities--and again

keeping to one side my determination that Restrictive Covenant 8 does

not preclude the keeping of a miniature horse--none of the plaintiffs

experiences any hardship by the Mignaccas keeping Sonny. Balancing the

equities, the Mignaccas have found a gentle pet and wholesome activity

for Christian, whose weak legs, problematic growth plates and braces

prevent him from participating in other competitive activities, such as

baseball and football, with his friends and other children of his age,

and this clearly outweighs the undifferentiated fears of the Homeowners

Association and the individual plaintiffs.

Plaintiffs argue strenuously, but without supporting evidence, that

Sonny will drive down property values, if not throughout the

development, at least regarding nearby homes. Based on the evidence

presented before this Court, Sonny's presence will cause no such

problem; but it is likely that if the Ridgewood Homeowners Association

develops a reputation that its leadership is unnecessarily and

unreasonably zealous and brings homeowners to court for unobtrusive

activities designed to meet the needs of a special child, then the

owners in Ridgewood may find the marketability of their premises

declining. Nothing in this decision is meant to suggest that Christian,

or any other child living in Ridgewood, can flaunt clear, sound and

appropriate restrictive covenants. If Christian wished to keep a herd of

cattle because he and his parents thought it in his best interest to do

so, or if he and his parents concluded that playing the drums in his

backyard at one o'clock in the morning was a satisfying and beneficial

activity, he would find no protection in this Court. He and his family

are protected here today for the reasons set forward above. Accordingly:

(1) In Ridgewood Homeowners Association, et al. v. Cranston Zoning

Board, et al., 01/PC-2241, pursuant to R.I.G.L. 45-24-69(d), this Court

affirms the ultimate decision of the Cranston Zoning Board of Review

respecting the lawful right of the Mignaccas to keep Sonny on their

property and house him in the shed they erected for that purpose, but

the case is remanded and the Cranston Zoning Board of Review is directed

to declare in their decision in their record of this case that because

the Mignaccas have well in excess of 20,000 square feet on which to

permit Sonny to amble and graze, Cranston Ordinance 4-2.1 precludes the

necessity of granting a dimensional or any other variance to the

Mignaccas, as that ordinance allows the keeping of a horse, even in a

built-up area, so long as the owner has more than 20,000 square feet for

use as a pasture.

(2) Because Restrictive Covenant 8 does not apply to Sonny, the pet

miniature horse, and because a number of sheds and cabanas exist

throughout Ridgewood in apparent violation of Restrictive Covenant 6,

which permits no exceptions, the temporary restraining order earlier

issued in this matter is vacated; and the Mignaccas may keep Sonny on

their property and house him in the ten by twelve shed that exists

there; and if further construction is required to complete the shed, the

Mignaccas may undertake that;

(3) The counterclaim brought by defendants is denied, as there has

been no showing that any of Rena Dresseler's animals are either

proscribed by Restrictive Covenant 8 or constitute a nuisance under

Restrictive Covenant 5; similarly, the plaintiffs are denied injunctive

relief regarding defendants' pet ducks, rabbits and fish, none of whom

have been proved to be a nuisance;

(4) Counts 5 through 14 of the plaintiffs' amended complaint are

denied for failure of proof; and this Court finds as a matter of fact

that the defendant Mignaccas maintain their property in a neat and

pristine way and keep it within the tenor of the neighborhood; and the

plaintiffs failed to show that any recreational vehicles or equipment

used for excavation or lawn maintenance are occasionally visible from

the street or readily visible by any abutting property owner; and they

have failed to prove that if they are occasionally visible to the

curious or the hyper-critical they constitute a violation of any

restrictive covenant or an eyesore; and indeed, most of the objects

complained of were stored in a garage, where there is ample room to

store the other objects observed carefully parked in the driveway;

Final judgment reflecting this decision shall enter today.

|